【 Habit à la française 】

18th century France.

Coat worn by Rococo aristocrats.

【 Garment specimen 】

【 sample 】

Produced with stiff wool

Produced with stiff wool

The above dimensions are the finished dimensions of the pattern.

Clothing before and after the French Revolution was designed with extremely narrow shoulders.

Clothing before and after the French Revolution was designed with extremely narrow shoulders.

If you look at the measurements alone, you may be surprised at how small they are.

I recommend choosing based on "bust" rather than shoulder width.

You should choose a size around +12-14cm (4.7-5.5 in) from your bust nude measurement.

For example, if your nude measurement is 101cm (40 inches), a size 5 or 6 would be a perfect fit.

Size 1 or 2 for 82.5cm(32.5 inches)

Size 3 or 4 for 91.5cm(36 inches)

From here, we will focus on the "sleeves" and "pleats" that are characteristic of the Habit à la française design.

【 Extremely curved sleeves 】

These sleeves are designed to enchant the most beautiful of aristocratic gestures.

When you put the sleeves in the habit, your arms will naturally lift up and correct your posture as if you are about to dance.

The sleeves ensure comfortable rein handling not only when dancing, but also when riding a horse, for example.

"Baroque dance" flourished as the court dance of the French aristocracy in the 18th century.

At the same time, it was the era in which "modern horse riding" was established.

The modern straight-falling sleeve was created in the 1930s.

Straight-falling sleeves may look beautiful on a mannequin.

In contrast, the curved sleeves of the Habit à la française show their true value when worn by a human and in motion.

It is a form rooted in the aristocratic culture and history of the Rococo dynasty.

(In the antebellum period, it was also incised)

【 Multiple folded pleats 】

The pleats at the hem are an important design feature that defines the back style of the Habit à la française.

The total length of the pleats measures a whopping 141.7in(360cm).

The narrow fabric of the time was used lavishly.

The miyufir-like pleats are not only decorative, but also express "the beauty that accompanies one's actions".

It responds to the nimble steps of a baroque dance, the pleats swaying in pliés and hervés.

It is the pleats that cut through the wind and make the dressage more graceful and daring, even as you gallop along on your horse.

At first glance, it may look like just another fancy antique piece of clothing, but you'd be wrong.

By actually touching and wearing the garment, you will realize that the design, which may look glamorous, also has a functional meaning.

It is truly the "most beautiful and attractive structure" of the 18th century aristocratic culture.

Clothing from 250 years ago has a beauty that only those who have put their sleeves on can see and feel, which cannot be seen just by looking at it.

5 ft. 7.7 in. 136.6 lbs.

172cm 62kg

male

Wearing 【Size 3】

Size 3 is true to size.

There is room for a shirt and vest.

However, there is no room for a jacket.

If you want to wear it more loosely, you may choose size 4.

ーーーーー

153cm

slender female

Wearing 【size 0】

ーーーーー

5 feet 2.99 in.

160cm

female

Wearing 【size 1】

This person has a large chest, so it looks a little tight around the chest area.

Other than that, it seems to be just right.

ーーーーー

4 feet 11.84 in.

152cm

female

Wearing 【size 1】

Size 1 is true to size.

ーーーーー

6 feet 2.8 in.

190cm

male

Wearing 【size 7】

The length and sleeve length seem to be just right.

However, the back could be a little more fitted.

This kind of arrangement is also recommended.

【 Example: Light alpaca wool 】

We also recommend making it in a lighter fabric, like a shirt. This one is made of washed alpaca wool. It is very comfortable to wear.

It is also recommended for Habit à la française to be arranged in a long length.

This is because Rococo menswear is designed to evoke the "femininity" of the modern age.

By lengthening the length, the pleats will flourish more and you will be able to wear it elegantly.

As an interesting arrangement, we also recommend that you produce "only the upper body".

It will turn into an antique classic blouson.

When you try it on, you will be surprised at how cute and well-balanced it is, even more so than you imagined.

Habit à la française is a very old and unique pattern among demi-patterns.

Therefore, it is widely popular among both beginners and advanced sewers because it can be made to look like Habit no matter who makes it.

It does not require advanced ironing techniques to make.

So, although it may look complicated at first glance, the structure is actually much easier to sew than a suit.

My sense is that it is similar to the way shirts and blouses are made.

If you have fallen in love with Habit, your "enthusiasm" is the shortest way to completion.

Please enjoy your failures and try your hand at it.

From here, we will get into the details of the Habit à la française.

【 Decorative buttons 】

Fashion was an art form in those days.

Buttons were glamorously made as a part of decoration.

【 covered button 】

It is a very elaborate creation, very different from modern walnut buttons.

Silver threads are woven into the wooden base and wrapped around it.

Beautiful silver thread weave pattern.

Four threads are woven crossing each other.

If you look closely, you can see a "raw core thread" among the silver threads.

The silver thread is wrapped around the core thread to make a single thread.

This is the back side of the button.

A rounded wooden base is placed inside and pulled by hemp threads to wrap the base.

Looking at the back side of the button, you can understand that it is very sturdily fastened.

I removed the hemp threads.

The button has a wooden base.

Wooden foundations were used in a wide range of clothes, from those of the nobility to those of laborers.

Each Habit à la française comes with 24 of these intricate buttons.

I wonder which is more difficult, sewing one Habit or making 24 of these buttons.

In most cases, the Habit à la française is worn open in front.

The most important garment in the 18th century is the "waistcoat" worn inside.

In other words, the Habit is like a frame in a painting.

It enhances the main subject of the painting.

Hence, the button also prioritized "decorativeness" over functionality.

In fact, many buttons are attached that do not function as buttons.

【 Unique roundness 】

The Habit à la française has no border between the shoulders and sleeves.

In modern suits, the shoulders and sleeves are separated and look like separate parts.

The Habit, however, appears to be smoothly connected at the shoulders and sleeves.

Placed on a flat surface, its unique roundness stands out.

The structure is designed to express the slender upper body and sloping shoulders that are the aesthetic senses of the Rococo aristocracy.

【 Mille-feuille pleats 】

Rococo masculine beauty was found in the lower body.

In contrast to the slender upper body, the lower body is fuller.

These mille-feuille folded pleats are the most distinctive feature.

This section is the most difficult part of tailoring the Habit à la française.

The pleats, which overlap up to 18 layers, easily break the sewing machine needle.

Of course, it was sewn by hand in those days, so it must have been really hard to sew.

The thickness of the actual product is as much as 0.79 in(2 cm).

Looking at the pleats from directly below, you can clearly see the overlap.

It is a luxurious mille-feuille of fabric.

【 Disassembled lower body 】

The fabric is used all the way to the edge without wasting any fabric, and is well divided and joined together.

"Yellow selvedge" can be seen on the edge of the fabric.

【 Habit's selvedge 】

It is a stylish yellow color.

By measuring the selvedge ends, you can calculate the width of the fabric at that time.

This silk velvet fabric was about 18.5 in (47 cm).

This narrow fabric was joined together to create a hem flare of 141.7 in (360 cm).

Pleats with large amounts of fabric overlap are very heavy.

To support this weight, the backside of the pleats has a complex structure.

A word of caution.

I own about 10 pieces of 18th century clothing, and what I present here does not apply to all of them.

The structure I am about to show you is only one example, but it is the most elaborate and interesting structure I have studied.

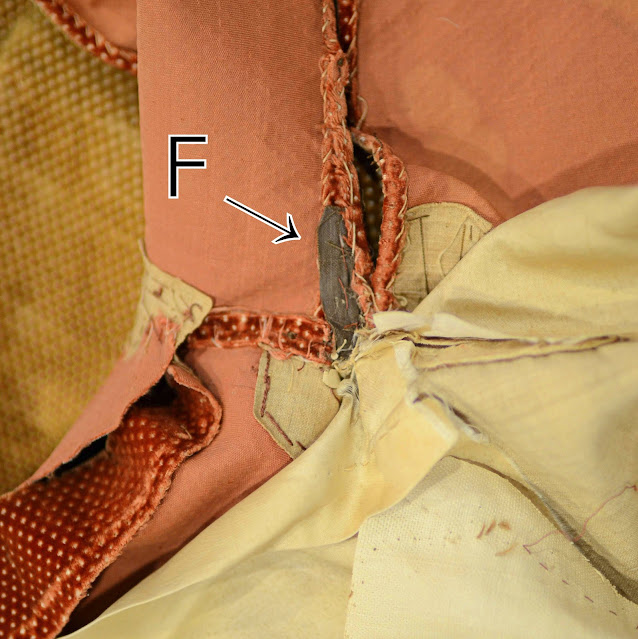

The following is a list of six distinctive structures, from A to F.

Each of them, viewed from the inside, is arranged like this.

First, let us explain the relationship between the first A and the last F.

These two structures are critical to support the weight of the pleats.

A is the seam that comes directly above the pleat.

This is thought to be an additional seam for added strength.

Antique clothing has seams in various places to save fabric and adjust the size, but this is not the case with this seam.

F is a thin chintz linen.

Let us look at the position of F from the inside.

As suggested by the explanation given in A, F serves as a core to merge the pleats with the upper body.

F is sewn to bite into the pleats and lift the pleats, and is sewn to the A seam.

Next are B and C.

B is a chintz linen.

C is a thick chintz linen.

The B sewn on the upper body is extended to the pleats on the lower body, as you can see in the photo above.

In other words, like F, it serves to reinforce the top and bottom.

C has two roles: reinforcing the pleats and reinforcing the pockets.

This linen fabric is firm and stiff.

C is enlarged.

C is also used for the front edge of the body.

D is paper.

In the modern age, we rarely see paper interlinings, but they are sometimes found in antique clothes.

D is just within the fold of the pleat.

Perhaps a paper interlining was used to bring out the folds nicely.

The last one is E.

E is the same chintz linen as B.

E stays at the base of the pleat.

The pleated portion has a total of 18 overlapping layers in the face and lining fabrics.

In addition, there is an interlining layer, which makes the pleated incredibly thick.

It must have occupied such an important position.

I respect the craftsmen of old who sewed these by hand.

And this waist switch likely took place in the late 1780s or around 1790.

It appears to have been remade to fit the style of the new era.

In 18th century men's clothing, all design points were low.

Waistlines, pockets, pleats, etc., were all low.

This is in stark contrast to 19th century menswear.

【 hollowed-out pocket 】

Pockets in the 18th century are made by hollowing them out.

They are not welt pockets as they are today.

It was not until the 19th century that welt pockets became the norm.

The back side of the hollowed-out pocket looks like this.

The cut is not strong enough, because the cut is made just as close to the edge as possible.

Because the fabric is silk, the pocket area is prone to tearing.

Sturdy welt pockets are a wonderful invention.

【 Disassembled upper body 】

Note the shape of the armhole.

Many 18th and 19th century garments have armholes shaped like this.

Many people look at this shape and think that the front of the armhole has been cut off.

In other words, the base of the arm is forward.

So, they think that the sleeves swing forward.

That is a big mistake.

This armhole is due to the extreme bending backward design.

A closer observation reveals that the base of the arm is backward.

The figure above shows the antique and new patterns overlaid based on chest circumference.

Dotted line is modern pattern, solid line is antique pattern.

When the ratio of the chest width to the back width of each pattern is calculated, it is clear that the antique pattern has a back width is narrow.

The figure also clearly shows that the armholes are placed backward.

What exactly is an extreme bending backward design?

Here is a brief demonstration.

【 Contemporary pattern 】

First, we have a modern armhole.

This is then transformed into the extreme bending backward seen in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

【 Transformed state 】

It is based at the base of the armpits and develops toward the neck and chest.

【 Drafting connected 】

Then, the armhole shape introduced earlier will be shown.

In terms of the design of the pattern, one could think of this development as taking place.

Of course, the same operation is possible with this other development.

This manipulation can then be used to narrow the waist, flare out the hem, or raise the chest.

Older clothes created a variety of shapes by making extreme bending backward designs.

So it has nothing to do with forward bent sleeves.

So how is the sleeve bent forward?

The answer lies in the sleeve itself.

The most important point needed to express this sleeve depends on whether or not a "triangular face" can be created behind the sleeve.

【 Triangular face 】

This triangular surface appears on the rear side of the sleeve.

This surface is huge until the beginning of the 19th century, gradually shrinking and disappearing around 1930.

Habit a la française fits the back.

Instead, it creates a triangular surface on the sleeves to ensure movement.

The approach to movement is much more effective when created on the sleeves than on the back.

The key to designing is V.

The V is the base point of the rear side of the sleeve.

It is not the position of the seam.

However, for men's clothing, the V is often used as the seam location.

Check the position of V on the pattern as well.

This is the V position.

The position of the V is very different between antique and modern clothing.

Check the height difference between the apex of the sleeve and the V position.

Checking the Habit sleeve, we can see that there is little difference in height between the vertex and the V.

However, when we check the height difference of the modern sleeves, there is a large difference.

In the case of women's clothing, this difference tends to be even greater.

Reducing the height difference between the vertex and V is an important aspect of creating a triangular surface.

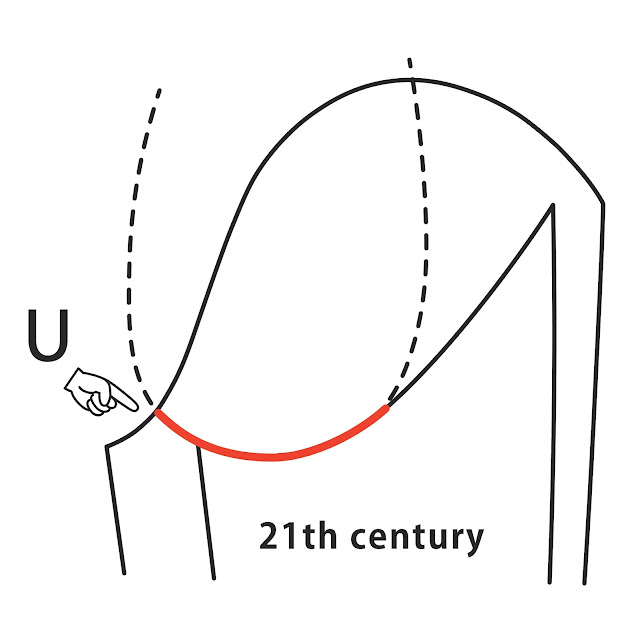

And U is the base point for determining the height of V.

U is the base of the front side of the sleeve.

It is the base point that comes near the base of the armpit.

U, like V, does not imply a seam.

However, in most cases, antique sleeves use the U as a base point to create a seam.

Check the modern U.

Using the U as a base point, we focus on the relationship between sleeves and armholes.

Now let's see if the antique U is a match.

They do not match at all.

The curves of the armhole and the bottom of the sleeve are far apart.

This results in a determined difference in the height of the V.

【 Disassembled sleeve 】

These specially designed sleeves are very interesting to wear.

At first glance, they appear to be tight, but in fact, once they are on, you can move your arms freely.

This comfort is what we want you to experience most at Habit a la Française.

【 Habit a la française fabrics 】

The smooth feel of the silk velvet is very comfortable.

The pattern that looks like white dots is a small perforation.

The white weft threads look like dots.

【 look through a microscope 】

The photo is rotated 90 degrees.

You can clearly see the white weft threads.

This is the true nature of the dots.

【 View Cross Section 】

A cross-sectional view from the side shows the raised velvet.

The part where the white weft threads are visible has been trimmed short.

【 See back side 】

Turn the fabric over and look at the reverse side.

You can see that the fabric is densely woven, although there is no raised surface on the reverse side.

【 Silk satin lining 】

In most cases, the lining of an habit à la française is also tailored in silk.

The lining of this Abi was silk satin.

The fine bristles wrap around the entire body for a rich and comfortable fit.

【 Lining selvage 】

I could also see the selvedge on the silk satin lining.

The color has been removed, and it has a pale pink color.

Surprisingly, "three gold threads" were woven into the selvedge.

It is a typical example of the Rococo aristocracy that even the selvedge of the lining was made so extravagantly.

These are the results of my research into Habit à la française.

I love these clothes from the bottom of my heart.

By deconstructing the habit, I have learned a great deal about Western history and aesthetics.

If the patterns I sell can help you, it makes me truly happy.

Thank you for reading.